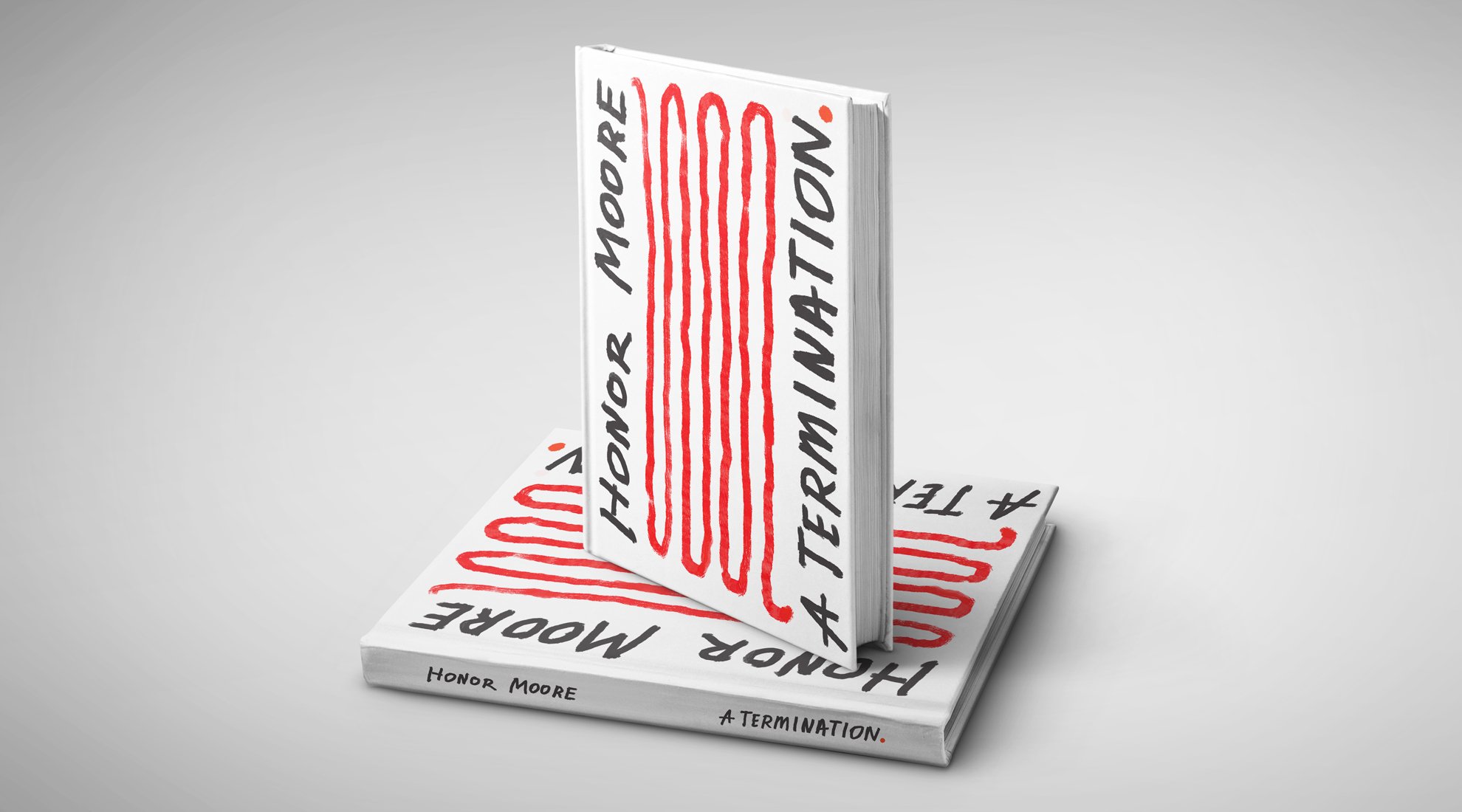

A termination

You can order A Termination on Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Books-A-Million, Google Play, Indiebound, Audible.com, bookshop, or through your friendly neighborhood independent bookstore.

a Termination.

Poet Moore (Our Revolution) meditates on the emotional consequences of her 1969 abortion in this exquisite memoir. After she became pregnant at 23—either by her older lover or a photographer she “unwillingly had sex with”—Moore was embarrassed to tell her parents, her lover, or most of her friends. She ultimately decided to terminate the pregnancy, obtaining a letter of approval from a psychiatrist after convincing him she’d “go crazy if I had a baby.” Following the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision overturning Roe v. Wade, Moore was moved to revisit the experience and put “a mirror to the past.” In fragmentary, lyrical chapters, she examines the feelings of liberation and fear her choice stirred in her, and imagines how her life may have unfolded if had she chosen differently. Piercing imagery (“Run fast, little girl, outrun rabbits and doctors, outwit them thoroughly”) and ruthless concision characterize Moore’s prose, resulting in an artful battle cry against backsliding into the secrecy of previous generations. Marked by Moore’s stunning balance of compassion and rage, this is a triumph. Agent: Rebecca Nagel, Wylie Agency. (Aug.)

At 23, She Had a Termination. 55 Years Later, She’s Ready to Write About It.

In 1969, Honor Moore was granted an abortion by a Connecticut psychiatrist, and went on with her life. In 2024, she reckons with the fallout.

When Honor Moore was a 23-year-old graduate student, she had an abortion.

It was April 1969, and the state of Connecticut allowed a woman to end her pregnancy if a doctor determined that giving birth would threaten the life of the mother. During an interview with a psychiatrist in a toy-strewn office in New Haven, Moore said she would go crazy if she had a baby, and the psychiatrist gave her a letter permitting an obstetrician to carry out the procedure.

Waking up in the hospital recovery room, she found a bouquet of flowers sent by friends and a furious doctor — he’d instructed her not to tell anyone.

Her friends visited anyway, bringing her a sandwich. And Moore continued her studies, spending the summer in the Berkshires as press agent for a glitzy play.

There are details Moore doesn’t remember — did the abortion cost $2,000? Did her gynecologist’s name begin with a “B”? She can’t be sure — because she didn’t begin writing “A Termination,” her slim, searching memoir of her abortion and its effects, until she was in her 70s.

In May 2022, when it became clear that American women would no longer be trusted with decisions about their pregnancies, Moore finished the book in a fever. What had her abortion meant to her? At 23, Moore did not know that she would go on to write six highly praised books of poetry, memoir and biography.

She had graduated from Harvard, torn theater tickets for a summer and won a place at Yale Drama School. She wanted to write, and although no one was stopping her, she had yet to begin.

Her mother, who had given birth nine times, sent her into the world with one instruction: Don’t come home pregnant. Her father, Paul Moore, the progressive Episcopal bishop in Washington and eventually New York, turned up monthly to take her to the movies but remained aloof. Perhaps she knew his views already: not in favor, but maintaining the right to abortion was a “decision of conscience.”

When Moore did become pregnant, she realized that however she counted the days she could not be sure whether the father was the photographer who had flattered her into bed for a single night or the professor she was in love with, who said he would have married her when he later learned of the abortion. She describes the situation as “a knot from which there are so many exits, there is none.” In not wanting the photographer’s child, she cannot have the professor’s child. In wanting her imagined future life, she can’t wholly abandon her former life. Abortion is revealed as a problem of love, born of sex.

A month before Moore terminated her pregnancy, a group of radical feminists calling themselves Redstockings gathered in Washington Square Methodist Church for an abortion speak-out. The idea was to talk about a common — but illegal — experience openly. Four years afterward, the Supreme Court finally accepted that the Constitution protects a right to abortion.

Moore didn’t understand what she did as political in 1969, and she wasn’t yet a feminist. “I didn’t have a self,” she writes of the 20-something Honor, and she comes to think of her decision to terminate part of her life and begin another as the first autonomous choice she ever made.

Feminism doesn’t create a demand for abortion, or turn it into contraception. (In fact, young Honor didn’t take her pill consistently, and her desire not to become a mother at 23 is a twin of her desire to sleep with two men.)

Rather, feminism allows a right to be applied equally across race, class and geography, something the women of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas and West Virginia were forced to learn again in 2022.

In contrast to “Happening,” Annie Ernaux’s slim memoir of a back-alley abortion in 1963 (and the basis of a movie by the same name), the tone of “A Termination” is hot and the chronology looping. Rather than a call to arms, or even a lesson from history, Moore’s memoir depicts her knot gradually and incompletely untangling over 50 years.

Her emotions remain mixed: shame, fear of exposure, sadness and a sense of freedom. In her head the aborted fetus has grown into an adult man who asks her why she didn’t have him. But both Moore’s and Ernaux’s experiences of abortion show that being able to end a pregnancy can be a necessary condition of women’s flourishing.

Moore remembers reciting her “matrilineage” in a circle with a women’s theater group in the 1970s: “I am Honor, daughter of Jenny, granddaughter of Fanny and Margarett,” she declared. Moore wrote a biography of Margarett (the painter Margarett Sargent) and a memoir of Jenny, but she has not become a biological mother herself. After she recounted her inheritance, everyone in the circle recited the same sentence: “I am a woman giving birth to myself.”

“A Termination” reveals what hard work that birth is.

By Joanna Biggs

Joanna Biggs is the author of “A Room of One’s Own:

Nine Women Writers Begin Again” and an editor at Harper’s Magazine.

“A distinguished poet and nonfiction writer reflects on the lasting emotional imprint of an abortion.

Moore, author of The Bishop’s Daughter and Our Revolution, was a 23-year-old student at Yale’s drama school when she terminated an unplanned pregnancy. The year was 1969, a time that also saw the emergence of the Jane Collective, a group that established an underground network dedicated to providing safe abortions to all women. Because the author was an “inheritor of minor WASP money,” she was able to get a legal abortion by convincing a psychiatrist that a child would destroy her mental health and paying for the procedure with her own funds. “There were two men who might have made me pregnant,” writes Moore: one a photographer who forced himself on her and the other, a professor who would have married her had she told him about the pregnancy. Early on, Moore unapologetically describes herself as Magdalene. “A taint of accusation hovers when I write about sexuality: She’s had bad relationships, they say. Fallen woman, the woman who sins, adulteress, slut, a stitch dropped from the fabric of society,” she writes. Even though she never wanted to have children, Moore returns to thoughts of the baby to which she never gave birth, imagining that child as a boy. “I was always looking for a great love—the kind that starts at a high temperature and calms over time, embers steady,” she writes. “What would I have looked for in a lover if I’d had a child?” The author’s candid, prose poem–like explorations of the ghosts of relationships past and the complexities surrounding love and sex for women make for compelling reading. But what makes her work especially affecting is the quiet way it suggests the possible shape of things to come in a post–Roe v. Wade era.

Haunting and lyrical.”

—Kirkus Reviews

Endings and beginnings

A personal story lies inside Honor Moore’s “A Termination.”

Memoir is rooted in memory, and Honor Moore’s new book, “A Termination,” dwells in its allusive and kaleidoscopic nature.

The termination she speaks of is an abortion, which she had in 1969 at age 23 — a theater student yearning for love and working for radical change but studying administration while harboring a quiet desire to become a poet. Now, 55 years later, Moore looks at her choices not just about abortion but relationships with lovers, sex, her own body, career path, and so much more, moving fluidly back and forth in time. She gives us linked associations in lyric prose rather than a straight narrative, with the leitmotif being the abortion and the child she might have had.

Moore drops us right in with her first paragraph:

“Not my lover, not my parents, and they said I couldn’t tell a friend. I remember my terror that the psychiatrist would not believe me. I’m sure I cried. I’m sure I told him I did not want to marry the father and was certain I could not care for a child. All of this complicated further because I’d unwillingly had sex with a man other than my lover, so I never knew who the father was, and there was no way to find out.”

Moore’s was no back-alley abortion. In 1969, all abortions were illegal in Connecticut, except in cases where having a child would threaten the life of the mother. She received one by convincing a psychiatrist of the necessity: “I must have said I was sure I’d go crazy if I had a baby since that’s what I assumed you needed to say to get what was called a therapeutic abortion. I must also have said I didn’t want to tell my parents.”

Moore became the poet and writer she longed for, and with sentences like this, you can see why: “It amazes me I didn’t tell anyone. I made the decision by myself. But also with the remote-control help of my mother: Don’t come home pregnant.”

She never claims to be the victim, however. “I didn’t think about I’m having an abortion, I just did it. Blasted through fear: I want this life, not that life.” And later, “I do not remember when my choice became a decision.”

Nonetheless, Moore gives life to the baby she might have had, imagining a son and conversing with him at various times. In one chapter, she writes two scenarios. The first is where she tells him that she and his father loved each other very much, but then they broke up and didn’t see each other again for a very long time.

Then she puts forth:

“Or I sit at the small table opposite my son and say, So, it’s time for me to tell you about your birth, and then I tell him about myself as a young woman, about loving L and about my naive encounter with the photographer, including that I thought seeing myself nude in photographs might reassure me about my body. What is he supposed to do with that? I want him to understand I did not know how to take care of myself. He was sort of a friend and I wasn’t attracted to him, I say; but before he took the photos, we drank scotch and I had my clothes off for the camera and we had sex that I didn’t want.”

Although she thinks about it, Moore doesn’t lament not having a child:

“There is a way I can speak that is stentorian, and when I do, I am not present: I never wanted to be a mother. Distinct from: I didn’t want a child.

I did not understand what it felt like to want a child.

I did not grieve the loss of my pregnancy, but I did grieve the loss of a younger self who had not yet made a momentous decision on her own behalf. A termination. A loss of innocence?”

Moore includes people’s reactions to her writing this memoir and what these conversations evoked. With a friend who tells her she wouldn’t have had an abortion:

“It was my first autonomous decision, I said, unsettled by her declaration. That’s what I’m writing about.

You were autonomous when you slept with the man who got you pregnant. She says this as a challenge. Almost hostile, which I know because my chest seizes, and my mind does that thing again, pieces of thinking clanging against one another, making what has been clear, blur and fog.”

At the same time, Moore owns what she chose to do and speaks to the larger contemporary political context: “Choice. I prefer the word decision, its etymology containing ancient words for strike down, slay, stab, cut. But the syllable also occurs in incisor, the cutting tooth. It is the privilege to be incisive that has been taken away.” “A Termination” is a way to take that power by making public what she had chosen to hide out of fear. She poignantly writes:

“What is it that remains unsaid?

At a table in late autumn, I make my way through what I have written here. Interesting how I can’t remember the beginning when I reach the end. It’s always that way, how you’re tossed forward to start again.

I did not tell, begins this book.

I’m telling you, ends the long-ago poem.”

By Abby Remer for MVTimes

Honor Moore by

Jennifer Cho Salaff

A memoir about a transformative abortion experience in 1960s America.

Honor Moore opens the door to her Upper West Side apartment, ushering me inside an eighth-floor oasis she has made cozy over the years with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves, handwoven rugs, paintings, family heirlooms, and framed photos of her many nieces and nephews. Barefoot and comfortably dressed, she settles into the sofa for what will be an animated, three-hour conversation about a decision she made when she was twenty-three, and how it has reverberated through her life since.

I met Moore during my first semester in the creative writing program at The New School, where she is on the graduate writing faculty. I was taken by her energy: bold, fierce, self-possessed, qualities that shine through in her seventh book, A Termination (Public Space Books, 2024). In this prescient memoir, Moore recounts undergoing an abortion in 1969, thrusting her into a churning cultural war that drew battle lines over feminism and reproductive rights. Tough, lyrical, and painful in its timing, this is the book we need right now.

Jennifer Cho Salaff

While reading A Termination, I kept thinking about something you have shared with us many times in class: we write memoirs to make sense of what happened.

Honor Moore

To figure it out.

JCS

The “figuring out” expands beyond the abortion itself. You write, “The book is not just about my abortion.” For me, A Termination is an exploration of the female body and what it is to live an independent life. It’s about agency, feminism, ambition, pursuing one’s dreams, and a woman finding herself—her Self. Of course, there’s also plenty about periods, birth control, orgasms, aging, and let’s not forget that fabulous souped-up Corvair!

HM

The Corvair!

JCS

I love that car. We’ll get to the Corvair. (laughter) You were figuring out so much during an iconic and turbulent decade in this country’s history!

HM

There was a huge sea change in the 1960s. The peace movement, civil rights, the women’s movement, the Stonewall riots, Vietnam, Black Panthers, sending humans to the moon; the assassinations of Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X; the anti-war protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Woodstock, all that music!

JCS

Speaking of music, I love that you wrote about seeing Janis Joplin perform at Tanglewood. “Like a flame across the dark stage—

HM

—an arsonist setting fire to herself.”

JCS

Your abortion took place in April of 1969, just before the moonshot and four years before Roe v. Wade made abortion legal. What prompted you to write this book, more than fifty years later?

HM

A reviewer of The Bishop’s Daughter (2008) wrote something to the effect of, “She glosses over her abortion, which is troubling.” I looked her up and found she was thirteen years younger and realized there was a big difference in attitudes toward abortion between my generation and hers. She didn’t understand that for women like me in 1969, having an abortion was like getting out of the draft. Boys were burning their draft cards, drinking beet juice to turn their urine red, and declaring themselves gay hoping to get a 4F, which meant you were “unfit for military service.” Managing to get an abortion was freedom from another kind of service! I wanted to go back into that experience and figure out who I was then.

JCS

You open with, “I did not tell . . . Not my lover, not my parents, and they said I couldn’t tell a friend.” You saw a psychiatrist who wrote a letter and sent you to an obstetrician who performed a “therapeutic abortion” in a hospital. What did the letter say? I imagine it was terrifying to be told not to say anything to anyone.

HM

I don’t remember what the letter said, probably formulaic. Because I was white and privileged, I had the means of paying for the procedure, having it in a hospital—which cost $2,000 in 1969, the equivalent of around $17,000 today. I remember the great relief of no longer being pregnant far outweighed any terror.

JCS

Your abortion was an act of self-determination; “Termination. As in, I hereby terminate one part of my life and begin another. Blasted through fear: I want this life, not that life.”

HM

I was the oldest of nine children. There was never quiet. It surprises me now that I had the courage and clarity to keep myself intact, that my dream of an independent life, of becoming a writer, had such force. That singular focus I had as a young woman was something I discovered while writing this book.

JCS

Which brings us to that blue Chevrolet Corvair. It appears nine times in the book. It’s this powerful symbol of freedom, empowerment, and independence. There are these memorable scenes of the narrator speeding down the expressway alone, blasting the radio, feeling a rush of solitude, quiet, calm. You write, “All summer, the young woman drove the blue Corvair up the valley to work and when she came home, she cooked, secluded herself in her bedroom, read, and sometimes wrote.”

The Corvair whisks you away, literally and metaphorically, toward a future of your own making: “. . . no almost-born child. Such a relief, my actual life. I drive the shimmery blue Corvair forward. I worry about what’s immediately in front of me, what I can see, but I do not concern myself with what’s behind me.”

You know, you’re the Corvair.

HM

The Corvair is definitely a kind of avatar for the young woman I was. (laughter)

JCS

Some of the most touching parts in the book are tender ruminations when the narrator imagines an alternative life. “Sun, son. I have always believed I would have had a son. Fifty-two years old by now, a physicist or a famous oncologist.”

HM

That part started as a typo. I meant to type “son” and it came up “sun.” Then I just left it.

JCS

Oh, I love that. A writer’s happy accident.

HM

I’m not sure I would have done that—sun, son—if it hadn’t been a typo.

JCS

The scenes where the narrator imagines this alternative life are some of the most raw, honest, and heart-aching parts of the book. In the chapter, “Mama Why,“ the narrator envisions herself having dinner with her grown son, she reaches across the table, holds his hands, and ruminates, “This is when he says, Mama, I want to know why you didn’t have me, which brings me to tears. I wanted all I hadn’t lived, but without displacing anything I have lived.” What was the experience like writing these scenes?

HM

I don’t write fiction so it was really fun conjuring up this nonexistent person. I had never imagined him, let alone brought him to life until I wrote this book.

JCS

It felt completely uninhibited.

HM

It’s true. I kept saying to myself, I am not going to scrimp on feeling free. And I let it rip.

“The anti-abortion movement at its root is about denigrating or suppressing the creative, the intellectual, the imaginative, the personhood of half the human race.”

— Honor Moore

JCS

This is your seventh book. Was it difficult, given the subject matter, to find a publisher?

HM

Fifteen publishers passed on it. I think several found the topic of abortion and the intimacy of my approach too controversial. My publisher of twenty years turned it down, which was a great disappointment.

JCS

And then you found the book a home at A Public Space.

HM

Thank god for the extraordinary Brigid Hughes, its editor, founder, and publisher. She understood what I was doing. She believed in the work.

JCS

And the book’s timeliness. I keep saying, This is the book we need right now! Its outspokenness. Considering what’s at stake today—the dismantling of Roe, the attacks on reproductive rights, freedom of expression under fire, banned books, jailed writers around the globe, and a consequential upcoming presidential election . . . what do you fear and what are you hopeful about?

HM

I fear totalitarianism. The kind of universe Margaret Atwood imagined in The Handmaid’s Tale. A friend of mine, a philosopher, puts it this way—those opposing reproductive rights privilege the animal function of women over everything else. The anti-abortion movement at its root is about denigrating or suppressing the creative, the intellectual, the imaginative, the personhood of half the human race. It gives me hope that the issue of women’s reproductive freedom has come to the center of the conversation, not just among women but for everyone.

JCS

Let’s talk about feminism.

HM

Yes! Let’s talk about it.

JCS

There’s a part in the book when you begin to “look for the feminists.” You write, “When I heard the words ‘the feminists,’ I got a chill. Glimmer of a self.”

HM

There was no feminism, for me, until after I left drama school and got to New York in 1969. Someone at Yale had said, “There’s something called Women’s Liberation,” so I went looking for it. I went to a speech by the late lawyer and now Black feminist icon, Flo Kennedy; I don't remember much about the speech, but she was so dynamic, powerful, and funny, she made me a little dizzy! Eventually, I started meeting women my age who were involved with politics. And then some of us ended up forming a consciousness-raising group.

JCS

What happened in these consciousness-raising groups?

HM

They were small groups of women, a dozen or so of us, who would meet every week in someone’s apartment. A topic each week: how you felt about work, your lover or spouse, your father, your mother, how you felt about abortion, marriage, having a child or not, how you felt about work. At the time it was all blazingly new. It was out of these hours of what we now call “sharing” that feminist consciousness emerged and feminist ideas evolved.

JCS

Whether you realized it or not, you were paving the way for Gen X feminists like me who grew up in the Reagan era and came of age in the nineties. For my generation, reproductive freedom, birth control, family planning, and a woman’s autonomy over her own body—these were all given, thanks to second-wave feminists like yourself.

HM

Feminist ideas about women’s health, for instance, emerged from women talking with each other about their experiences of healthcare—male doctors who didn’t listen, and the inadequacy of reproductive healthcare. That movement led to the medical profession encouraging patients to be involved in their own care and understanding that their body is their own. These were radical concepts. It started with the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, which published a pamphlet that evolved through editions, becoming the internationally best-selling book, Our Bodies, Ourselves.

JCS

Speaking of our bodies, there’s this powerful revelation in the book: “This was a new body I couldn’t get enough of . . . It was as if I had new skin, new hair, new insides. What had been an object of contempt now became a means of ecstasy.” What was that like, discovering what your body was capable of, this “ecstasy,” namely, the orgasm?

HM

I barely knew what an orgasm was. My body started to shudder of its own accord and it wasn’t until later that I understood what was happening to me. This was 1967, and women were barely even talking about orgasms.

JCS

You document these sexual explorers—William H. Masters and Virginia E. Johnson, who are described in the book as the “equivalent of pre-Columbian mapmakers.” Mary Jane Sherfey, the “Columbus of the clitoris;” and Anne Koedt, who wrote an essay, The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm, which came out as a pamphlet in 1968.

HM

Right—that thinking was very important—one of the many instances when an experience I had suddenly had a name, had nuance—there was new terrain to be explored. Audre Lorde’s essay, “The Uses of the Erotic” (1978), is a wonderful articulation of that thinking.

JCS

The narrator is a young woman who comes to understand, deeply, that she has a Self. There are so many places in the book where you write powerfully about agency. I think the sentence that packs the most powerful punch is, “I am a woman giving birth to myself.”

HM

That sentence is not original to me—I first heard it at a rehearsal of The Daughters Cycle (1977) by the Women’s Experimental Theatre.

JCS

I think A Termination is an unapologetic celebration of femaleness. One of my favorite lines in the book is, “I am Margaret Fuller and I accept the universe.” This one just stood out to me. The self-possession behind it.

HM

In the 1965 play, Calm Down Mother by Megan Terry, Margaret Fuller says, “I am Margaret Fuller, and I accept the universe.” She’s talking about a self that integrates mind, body, and imagination. These were new ideas and discoveries of that era. The narrator in A Termination is in the process of taking ownership of her body and integrating her body with the rest of herself.

JCS

I am Honor Moore and I accept the universe.

HM

Yes, I do! (laughter)

Video by Alyssa Shea

Music composed by Joshua Shneider